Inspired by silenceinbetween’s lovely post Current Understanding of Biology, I thought I’d write up a snapshot of my current understanding of neuroscience. Caveat: this will be written mostly off the top of my head, so excuse any typos or nonsequiturs.

I started “studying neuroscience” a few years ago, as in, I began reading an intro textbook a few years ago. I wrote about it early on in A foray into neuroscience and more recently in Textbooks as a preventative for depression, although the latter is more about the motivation behind reading a textbook.

I’m almost done now (98% of the way through) finished as of 1/4/2023, so here goes.

Basic facts

Neurons

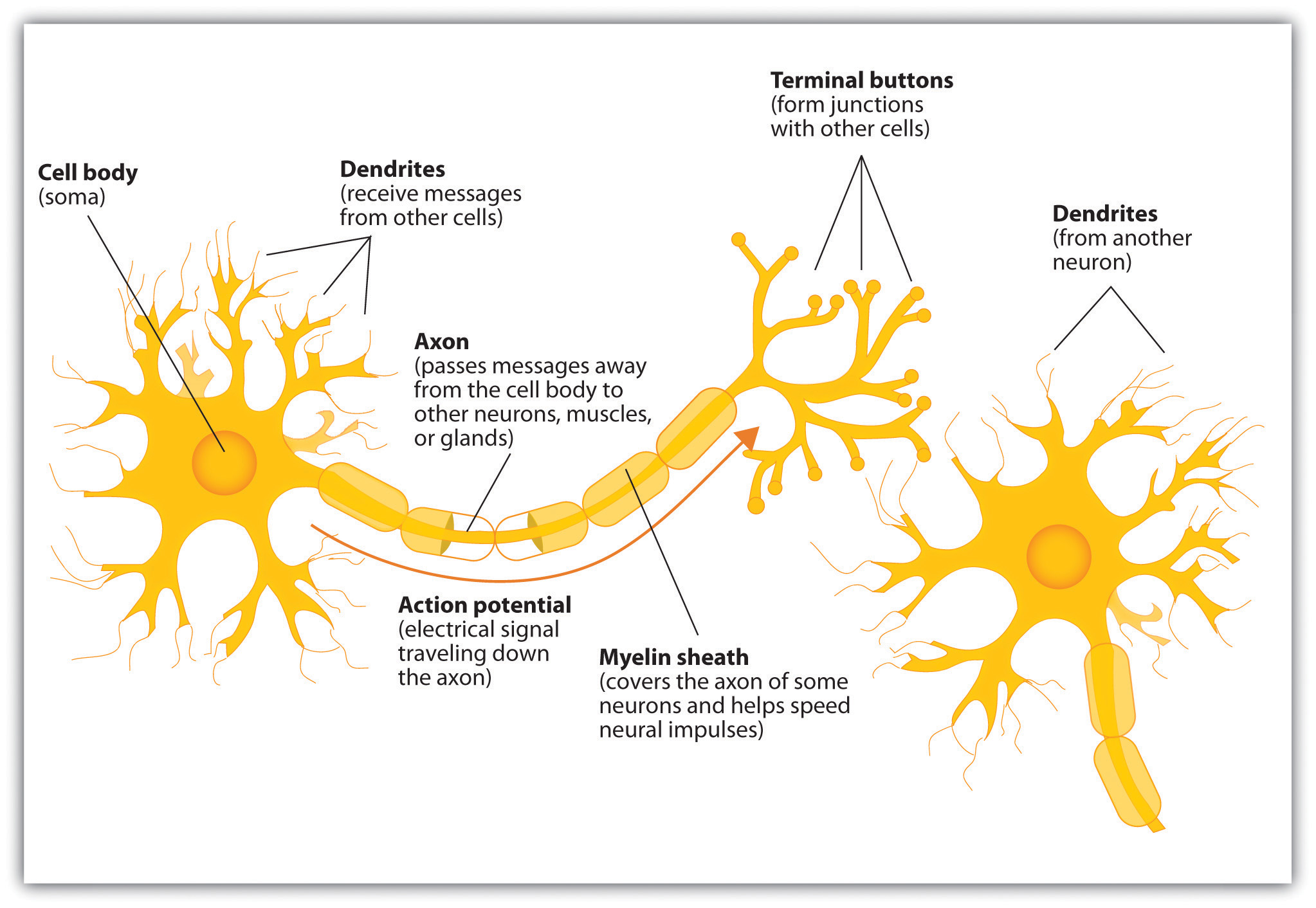

So, what’s the deal with tbe brain? It contains about a hundred billion neurons, and neurons connect to each other via synapses. Each neuron has a cell body, dendrites which take input, and an axon which produces output.

The basic anatomy of a neuron

The basic anatomy of a neuron

A note about anatomy which confused me at first: while the cell body projects into one axon, that axon can subsequently branch and form synapses with multiple further neurons. That’s why we say the neuron has one axon even though it may ultimately feed its output to multiple neurons. Dendrites, on the other hand, are present aplenty in each neuron, sometimes in the tens of thousands.

This is all well and good, except for the fact that there is this whole other category of cells in the brain called glia, and we’re not 100% sure about what glia do. They help insulate axons, “regulate extracellular space”, and perhaps other stuff? Some neuroscientists think glia will turn out to be much more important than we currently understand.

With that picture set, let’s talk about some high-level takeaways and questions.

Action potentials

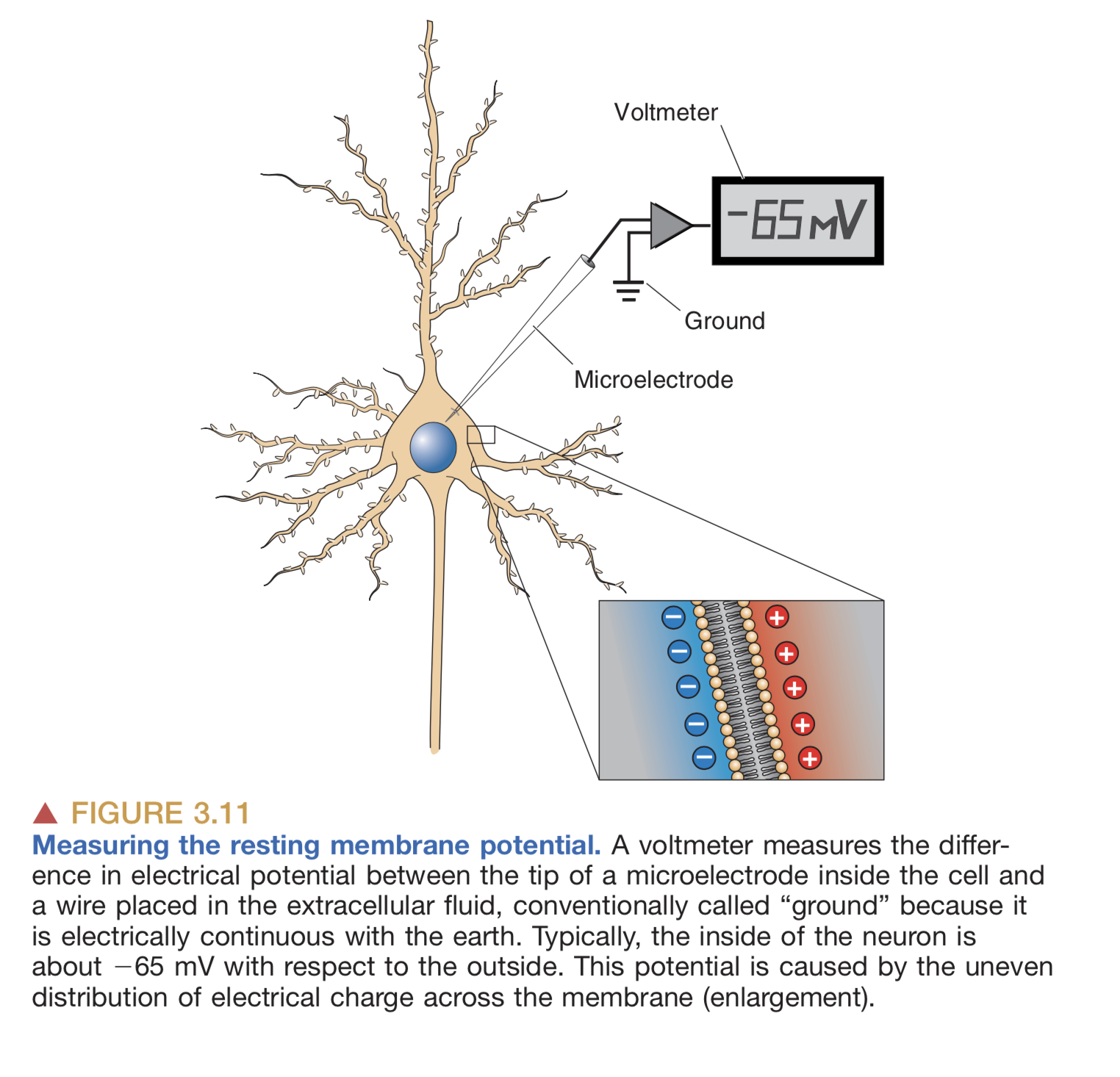

Action potentials are how neurons transmit information. Let’s explain what an action potential is. Neurons by default have an imbalance of charge on their membrane: the inside has slightly more negative charge than the outside:

Neurons by default have slightly more negative charge on the inside than the outside

Neurons by default have slightly more negative charge on the inside than the outside

By a series of complicated steps that I won’t get into here (which involve the passive and active transfer of ions through ion channels and transporter proteins in the neuron’s membrane), an “action potential” is a brief, sharp reversal of this electrical imbalance that propagates through the neuron’s membrane like a wave. See this GIF:

This “travelling reversal” of electric charge is what constitutes an action potential on neurons.

This “travelling reversal” of electric charge is what constitutes an action potential on neurons.

One other thing I should mention is: once the action potential has reached the end of the axon, there’s a whole other process for passing information onto the next neuron. Instead of directly creating an action potential on the next neuron, the axon releases chemicals into the synapse. We call these chemicals neurotransmitters. The effect of the neurotransmitter is to trigger an action potential on the next neuron, assuming there is sufficient neurotransmitter to actually trigger the neuron.

(Some more details: a little bit of neurotransmitter slightly depolarizes the target neuron, i.e. it begins to reverse the default electric charge imbalance. As more neurotransmitter builds up, the reversal of charge goes further and further until suddenly, it’s strong enough to trigger a full action potential on the target neuron. Note that some neurotransmitters have the opposite effect: instead of reversing the target neuron’s polarity, they actually increase it, i.e. they make it harder for the neuron to have an action potential. Each neuron takes inputs from many preceding neurons, and the synapse for each of these preceding neurons is either inhibitory or excitatory.)

Measuring the brain

Our ability to measure neural activity in humans is quite crude. Part of this is a technological limitation and part of it is ethical. With humans, we generally avoid doing anything invasive on the brain unless we absolutely have to (e.g. to treat severe forms of epilepsy or treatment-resistant depression). We don’t just cut out large pieces of the brain willy-nilly and see what happens (not anymore, at least).

So instead we measure the brain indirectly:

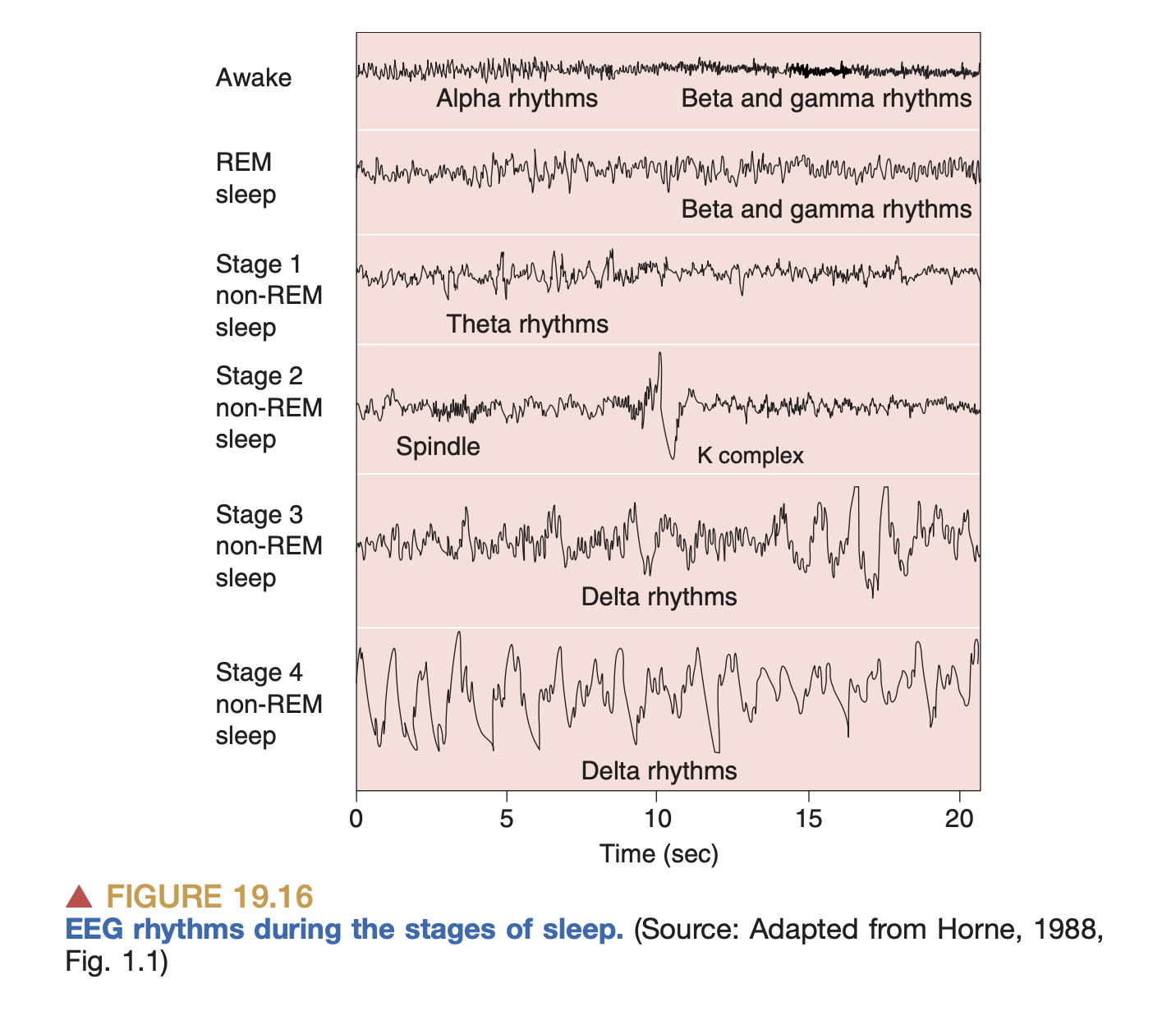

- Electrical activity (EEG): we tape electrodes all over the scalp and measure changes in electrical potential. Unfortunately, the electrical potential variations of an individual neuron are far too small to be measurable from the scalp, so the EEG is really measuring the aggregate activity of large numbers of neurons.

- This is why you see “brainwaves” on EEG recordings: neurons are only measurable if hundreds of thousands of them are all firing in harmony, and as it turns out the brain does have these synchronized patterns of activity at a few distinctive frequency & amplitude combinations (we call these e.g. alpha waves, beta waves, and so on.)

EEG measurements during sleep. We just get a high-level picture of activity

EEG measurements during sleep. We just get a high-level picture of activity - We can also implant electrodes directly onto the brain (ECoG), which gives us much more fidelity in measuring action potentials. This is what Neuralink does to, e.g. determine which direction the brain wants to move a joystick.

- EEG measures electrical activity, while MEG measures magnetic activity (wherever there is a changing electric field, there will also be a magnetic field, so they are effectively measuring the same thing).

- This is why you see “brainwaves” on EEG recordings: neurons are only measurable if hundreds of thousands of them are all firing in harmony, and as it turns out the brain does have these synchronized patterns of activity at a few distinctive frequency & amplitude combinations (we call these e.g. alpha waves, beta waves, and so on.)

- Blood flow (fMRI): using magical physics, we measure the flow of blood in different regions of the brain, which supposedly gives us an idea about what brain regions are most active.

While fMRI provides higher spatial resolution, EEG and MEG provide higher temporal resolution.

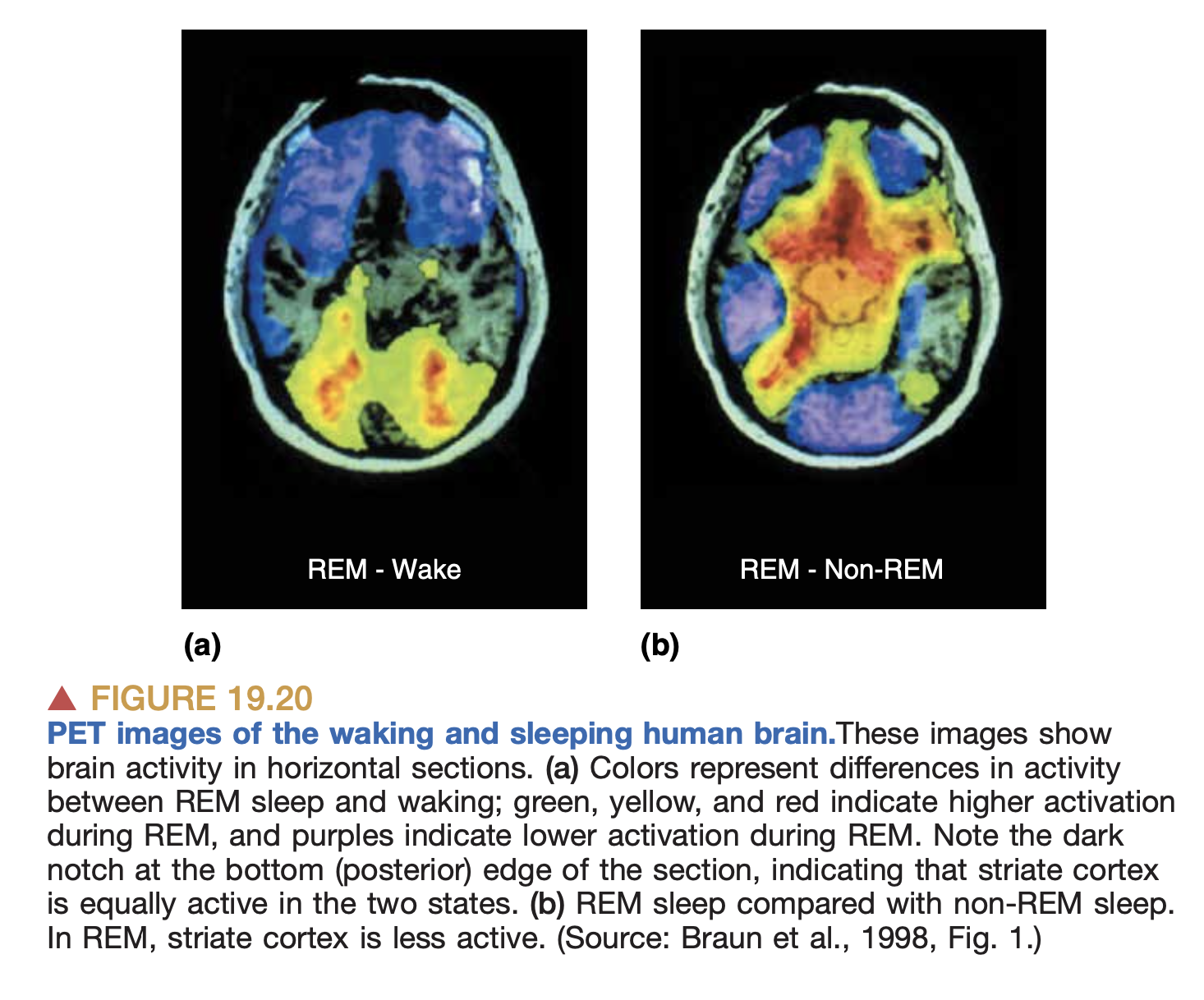

PET imaging during sleep.

PET imaging during sleep.

There are other techniques too like PET scans, but the above seem the most common.

Outside of humans (and occasionally in humans too, via measures like Deep-Brain Stimulation), we do more invasive things like inserting electrodes into random places in the brain, or modifying the genes of the animal so as to make their neurons triggerable via light.

Commentary

The significance of action potentials

One question worth asking: is the propagation of action potentials the correct way to understand what the brain is doing? Is this the building block of the brain’s information processing capacities?

I think the canonical answer is: yes. I haven’t heard of any other proposals for the fundamental unit of information processing in the brain. But, I’ve gotten the sense that individual neurons are doing a lot more computation internally than we previously believed. And in any case, until we have a good understanding of how the brain actually performs its functions (intelligence, consciousness, thought, perception) as an aggregate of action potentials, we can’t be totally sure that this is the correct building block.

How do we know that action potentials are the relevant frame of analysis? From what I’ve seen, one thing we’ve established quite clearly is that our sensory systems transmit information to the brain via action potentials. (And in the other direction, our brain transmits commands to our muscles also via action potentials.) In particular, each of our sensory systems is really just a system for transducing action potentials from some other kind of signal in the world:

- In our eyes, we have proteins which allow ions (charged particles) to pass through a membrane based on the amount of light they’re receiving. In other words, we’re converting light into action potentials.

- In our ears, we have these tiny hair cells which move ever so slightly as a result of vibrations in the air (which first propagate through a series of intermediate media like our eardrum, a few tiny bones called ossicles, and then a viscous fluid in the inner ear), and this movement triggers a change in electrical potential on the hair cells.

- In our nose, we have ion channels on receptor cells that open or close based on the presence of specific chemicals, such that the chemical itself (the odorant) triggers movements of electrical charge which propogates to neurons. (Fun fact: the sense of smell is the oldest of all senses evolutionarily, so the apparatus is the most “primitive”, compared to e.g. sight or sound. With smell, there is no elaborate machinery for converting signals from the world into action potentials, it’s a pretty direct conversion.)

For more, see sensory neuron and sensory transduction wiki pages.

So one way you could think of the brain is: convert signals from the world into patterns of charged particles moving back and forth on neuron membranes in complex ways, and then convert those patterns into muscular contraction which allows the organism to move about and act in the world.

Another line of evidence of action potentials being the fundamental operating unit of the brain: the brain-machine interfaces we’ve successfully built so far (e.g. Neuralink) operate by measuring changes in electrical potential on neurons, AFAIK.

Macro versus micro

One general takeaway from reading the book: our understanding of the macro is much worse than our understanding of the micro. There are open questions at all levels of granularity, but at the higher levels we don’t even have an operating framework for how the brain does any of the things we care about. We understand the mechanics of individual neurons fairly well, but at the level of the whole brain, we have some very rough ideas like “the cortex seems to be where the higher-level processing happens”. Well, let’s actually list out what we know about the higher-level properties of the brain:

- Certain regions are specialized for specific kinds of activity. Some clear-cut examples:

- The cerebellum is where motor commands from the cortex are translated into individual muscular movements. This region is responsible for the pure, mechanical function of coordinating our muscles to move in the way we intend them to. This involves a lot of computation.

- The brainstem is where functions vital to survival are (heartbeat, breathing, etc.). If you lose your brainstem you die.

- And then there are other regions which, AFAIK, are also specialized, but the boundary is much less solid, and other regions can sometimes compensate if they are damaged. Examples:

- The visual cortex processes visual input. It’s located at the back of your brain. (There are actually several areas of cortex involved in vision, ranging from “low-level” visual processing of lines and shapes to “high-level” processing of objects and faces.)

- The auditory cortex processes sound input.

- A few regions of cortex are responsible for language (Wernicke’s area, Broca’s area).

What’s the deal with the location of the different regions of cortex, e.g. why is vision in the back? It’s actually just a matter of where sensory neurons tend to end up in the cortex. So the visual cortex is in the back because the optic nerve takes input from the eyes and projects it all the way to the back of the head, and so on.

How do we discern that a given region is responsible for a given function? Either by finding that it’s more active in specific tasks (as measured by fMRI), or by finding that when that region is damaged, the corresponding function is damaged. See Are lesions a good proxy for brain function?.

What part of the brain is involved with consciousness?

We really don’t know. Some people claim it’s the cortex, some people claim it’s the thalamus (which acts as a kind of “relay switch” between cortex and sensory organs), some people claim consciousness is everywhere, some people claim it’s in the midbrain.

How does the brain learn?

This is one of the spicier parts. Here’s the basic picture we have right now: we learn by modifying the weights of connections between neurons.

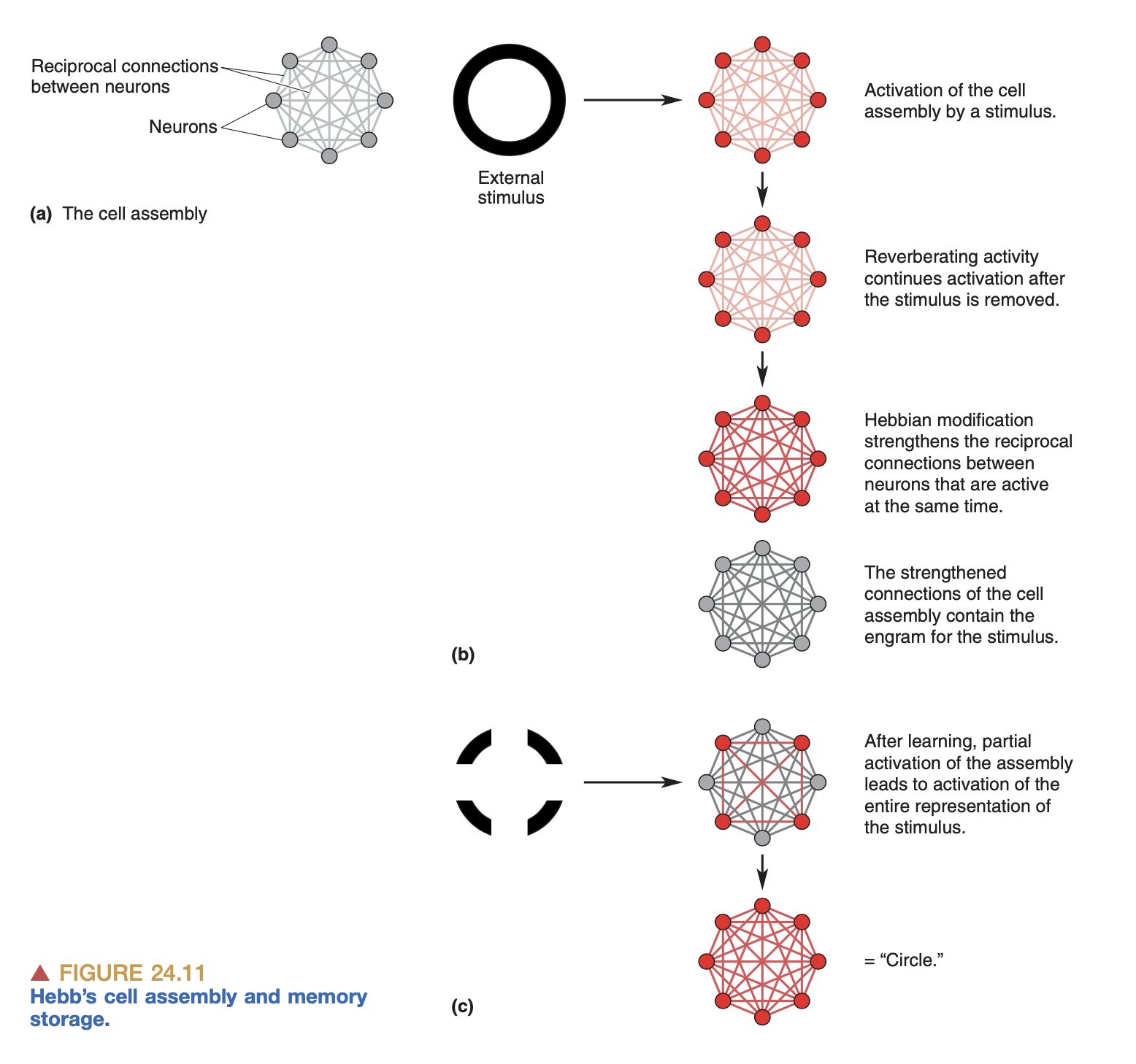

Hebbian learning is a major theory for how weights of neural connections are modified. In short it says: neurons that fire together wire together. Suppose neuron A synapses onto neuron B. Hebbian theory proposes that if B fires immediately after A fires, and this happens repeatedly, then the connection between A and B get strengthened.

Hebb proposed his theory in the 1950’s, and a few decades later it was developed further into BCM theory, which is Hebbian learning but with additional theses for weakening synapses as well as strengthening them. BCM theory states that if neuron A fires but neuron B doesn’t, then the synapse from A to B gets a little bit weaker. Or, if neuron B fires right before neuron A fires, the synapse from A to B also gets weaker.

The general idea is that in this way, the brain adjusts its weights and it learns. This is how current deep learning models work: the magic is in the weights of the connections between nodes; the “memory” of the network is in the set of connections and weights of each of those connections. (See my notes on AI.)

This is a connectionist or associationist picture of learning. Crucial to this picture is the idea of cell assemblies as representations of objects or ideas. So, if I see a picture of my grandma, there’s a specific set of neurons that are active in my brain, and this is what represents my grandma. And then, if I later just think about my grandma, the same assembly is activated. Memory is just the linking of various sensory inputs together.

The Hebbian cell assembly

The Hebbian cell assembly

There are plenty of things here that I don’t understand. For example, if a given assembly is the representation of my grandma, how do transformations to that representation take place? If I imagine my grandma drinking water, does that involve the assemblies for “grandma”, and “water”, and “drinking” all being active at once?

While this is the predominant theory for how the brain implements memory, there are people who disagree. Randy Gallistel, for example, claims that the brain does not learn merely by forming associations in sensory input, but by storing abstract information inside individual neurons. Wow! I don’t understand his theory in any detail, and my next task is to read his paper.